This post is not for everyone. If it’s for you, you’ll know. You’ll have that little feeling, the one you get when you’re faced with a decision but already know what you’ll do.

This post is personal and vulnerable. It’s also long and a bit self-indulgent: I talk about myself A LOT. This should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: If you don’t want to read this, you don’t have to.

Think of this as the first draft of my “big story,” the one I think I’ve been put on the planet to tell. Getting it onto paper this way was cathartic and challenging. It was an attempt to create a masterpiece when I haven’t yet put in my 10,000 hours of work (and it shows). I have been playing with some of these ideas for a long time, and I plan to explore them more in the future.

I feel compelled to attempt to tell this story now, even though it’s imperfect. Consider it a leap of faith, a moment of trusting my intuition in the absence of external validation.

To compensate for any obscurity in my writing, here’s a quick outline of the core argument that I’m making here:

Music can evoke an emotional response in the listener.

As music’s complexity increased, so did its emotional nuance.

Because of the power of music to create an emotional experience in the listener, music can generate emotional healing and self-acceptance.

Music may be able to go even further than affecting our emotions: it may be able to change our state of consciousness.

This may be why music evolved in humanity: to help us change our minds and elevate our consciousness.

Music doesn’t just change the mind, it activates the motor parts of your brain. Music literally moves you to take action, to dance.

Perhaps by dancing to incredibly creative, inspired music, we can save ourselves, and thus, the world.

This post mixes rationality with mysticism. I think both are required to understand the truth of our reality.

By telling my story, I hope to start more conversations about the transformative power of music. I would be thrilled to hear your story too.

With love,

Mia

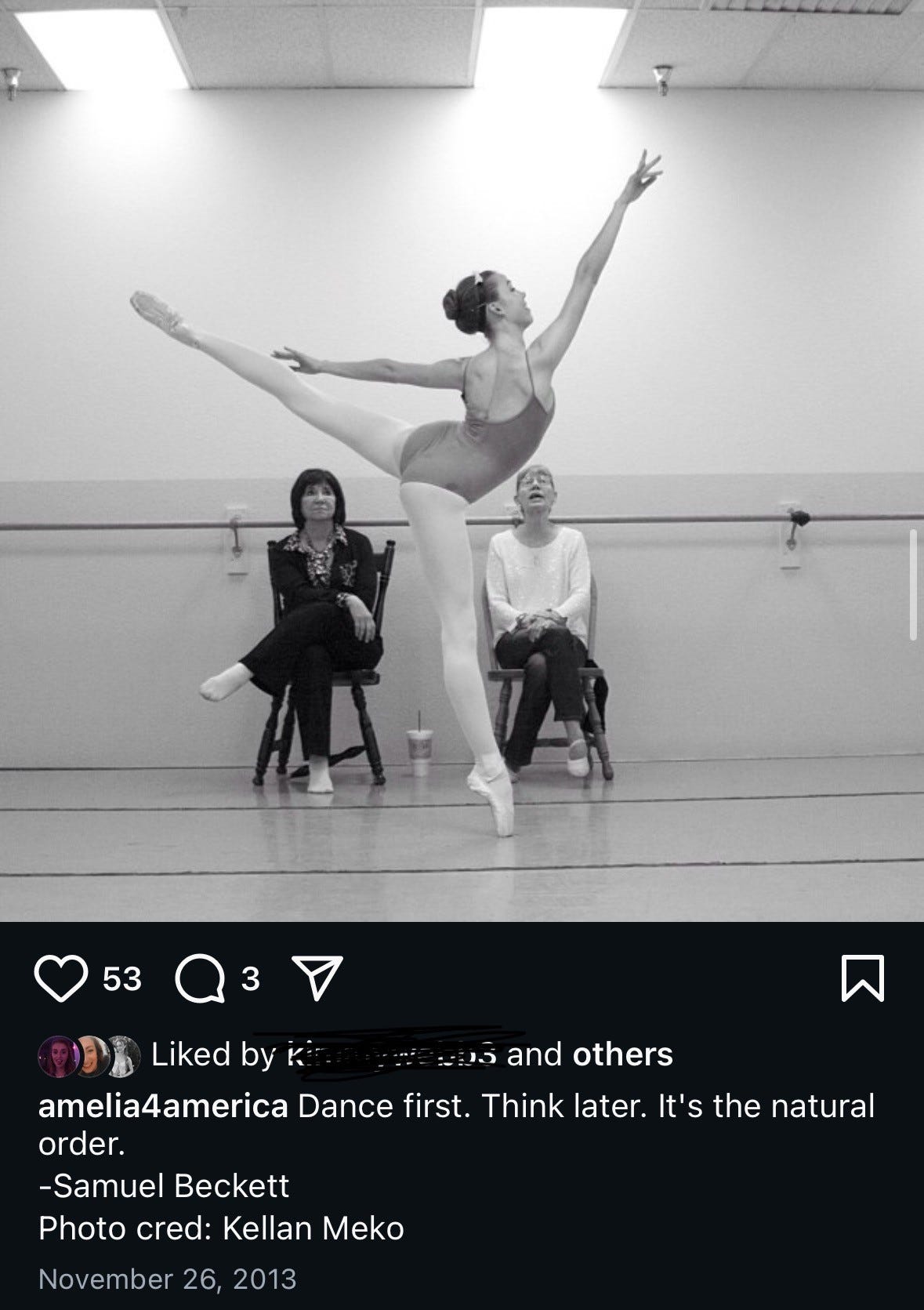

I think dancing is cosmically important. But perhaps I’m biased.

Like many little girls, I took a dance class when I was in kindergarten. According to my mom, our teacher selected two-piece bikini costumes for the big recital, but the mothers revolted. After all, we were only five. So instead our bodies were safely covered in little dresses as we danced to Sesame Street’s “Fuzzy and Blue.”

Following the great bikini incident of 2002, my parents pulled me out of dance and pushed me into sports. Unfortunately for my father, I hated them all (sorry, Dad!). So, it was back to dance class—skimpy costumes and all. Music was a big part of my childhood: I played the piano and the clarinet, joined the Phoenix Girls’ Chorus, and sang in church as part of the worship team. But when the time came to narrow down activities and get good at something, the answer was obvious: I would keep dancing. What started as a weekly hour-long combo dance class ballooned into over 20 hours per week of ballet class and rehearsals for performances like The Nutcracker, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty. A few girls I danced with now dance professionally at top companies like the New York City Ballet. But I wore pointe shoes for the last time the summer before my freshman year of college.

My personal Dark Ages followed.

I moved across the country for college, but I may as well have moved into a different reality. I grew up in a very conservative, Christian home and attended schools founded by my church. I had my doubts, of course. Every Sunday morning before church, I felt sick to my stomach, something that I started to conceal out of embarrassment when I was in middle school. In high school, I began to struggle to fit into the conservative Christian female mold that so many others seemed comfortable with: I’ve always been strong-willed and couldn’t imagine being in a relationship with someone who expected me to “submit” to them. But it was still the only culture that I knew. I wasn’t exposed to underage drinking, premarital sex, or even the theory of evolution. Then, through some combination of hard work, a bit of luck, and an intuitive nudge, I ended up in college in DC. I realized almost immediately that I was alone and woefully unprepared, both academically and socially. Anxiety gripped me constantly. I made the mistake of trusting someone who was comfortable in this unknown culture; I thought he might help me fit in. He instead took advantage of my naivete and nonexistent tolerance to alcohol. The days that followed were some of the darkest in my life: I couldn’t sleep or keep any food down. My worldview broke down: I knew that I was no longer safe.

I tried to flee back to whence I had come: I surrounded myself with Georgetown’s most conservative Christians. I started dating the president of the pro-life club. In the beginning, it seemed like he was obsessed with me and supportive of my dreams. Over time, he became jealous, then controlling, then emotionally abusive. Our arguments were heated. At some point, he started to hit me. By then, he had already emotionally isolated me from my friends and family. And so, I prayed. I prayed for divine intervention, that one of my friends would suspect the truth and try to help. But, I was on my own. One day, we fought on the phone while he was out of town. He got in his car and started to drive home. I had a thought that didn’t seem to be my own: “This is not your heart’s desire.” I fled.

Chaos and self-destruction governed the time that followed. My ex had prohibited me from going out and dancing, and I reveled in my newfound freedom. I started blacking out once or twice a week. I started chasing pleasure and validation from unreliable men. When the pandemic started, my three-legged stool lost a leg: there would be no more dancing, just drinking and “dating.” My mental state was in shambles, and I knew something needed to change.

I left my prestigious political job for the private sector. I could work remotely from Phoenix, where pandemic restrictions were looser. My dad and I went for a hike every day after work. I met someone at a bar and felt a genuine spark. The first time I slept in his bed, I fell asleep instantly: my body knew I was safe. He and I muddled through a messy talking stage and built a stable relationship. And then, he took me to my first festival.

Music and emotion are closely intertwined. You can likely relate to the idea that music can alter your emotional state: songs that sound happy can make you feel happy, while songs that sound sad can make you feel sad. There’s some debate over whether songs that evoke “negative” emotions like sadness and anger are helpful: do these songs help us process and move on from these negative emotions, or do they deepen and lengthen our experience of them? But there’s little debate over whether music can change our emotional experience.

The music at my first festival—Decadence AZ—didn’t make much of an impression. But I knew that I wanted to give those happy pills another whirl. At DC’s first-ever Project Glow in April 2022, I candy-flipped for the first time and was introduced to Seven Lions (and Above & Beyond and GRiZ and Slander). The experience undoubtedly changed the course of my life. I remember feeling joy, awe, wonder, and gratitude. Afterward, I started making a playlist of songs I had heard for the first time. I broke down with tears of gratitude numerous times while putting it together. (Unsurprisingly, Seven Lions’ “First Time” is the playlist’s opening song.) That summer, whenever I was feeling down or stressed, that playlist could make me feel high. My body felt lighter; my thoughts were more positive.

The music could dramatically change my emotional state. But how? It hadn’t been my first time experiencing chemically-aided ecstasy or hearing beautiful music. But it was my first time hearing this music, this attempt to capture the feelings of awe, wonder, and love. And, my brain was primed for plasticity and positivity at the time of original exposure. For me, it was a recipe for emotional uplift.

I sincerely believe that if Beethoven were born today, he would be an EDM producer and DJ. Beethoven was a renowned pianist, but he didn’t just compose piano concertos: he wrote full-orchestra symphonies that used a variety of instruments to create rich and diverse sounds. He’s among the greatest musicians of all time, and it’s no coincidence that the musical geniuses of yesteryear—Bach, Beethoven, Mozart—were composers. They were not just songwriters, vocalists, or instrumentalists: They organized sound into symphonies using a variety of instruments. This allowed them to create increasingly complex music that could convey more elaborate stories and nuanced emotions.

Consider the so-called “fate motif,” the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Described as “the sound of Fate knocking at the door” allegedly by Beethoven, the sound seems to evoke the emotion of “fear.” But it’s not the sound of “terror,” but the sound of “foreboding.” That is, these seemingly simple sounds have a complex interpretation in the human brain: we do not just feel a simple sense of fear, but a sense that something dreadful is coming.1 This complex interpretation may not come through if these notes are played by a single instrument, or even by a few instruments with higher pitches than the standard cellos, violas, and double basses. But when the instruments are combined in a certain way, the magic happens.

Today’s EDM producers have greater creative flexibility and capacity than the great composers of yesteryear. It’s not just that they can use the sounds of any musical instrument in the world: they can create any sound imaginable. This ability to meld together sounds from familiar and unfamiliar musical instruments has led to a creative explosion in electronic music. The flexibility of EDM production has generated music that can convey a grander spectrum of emotions and ideas—and perhaps can even reintroduce a traumatized human to the feeling of joy.

Given my background, it’s unsurprising that melodic bass—EDM’s “worship music”—drew me in. After Project Glow, I remember googling whether Seven Lions was raised as a Christian (I didn’t find anything definitive). I don’t know enough about music theory to explain the technical details, but popular Christian music and melodic bass share many similarities.

Melodic bass is worship music on steroids. As I listened to my Project Glow playlist day after day, week after week, I refamiliarized myself with how it felt to be joyful. I remembered how it felt to be awestruck. I felt incredibly grateful that I had experienced something so beautiful. With repetition, those pathways in my brain strengthened. After a few months, I stopped listening to the playlist every day as I noticed its effects wane. But my joy wasn’t fading. Rather, it seemed everpresent, such that the music didn’t change its level as dramatically anymore. With the help of musical repetition and a single day of chemical enhancements, I rewired my brain for joy. This was more than a temporary change in my emotional state; it was something deeper.

Because music can evoke and affect emotion, it can change how we relate to and understand ourselves. Consider Inside Out 2, which explores the connection between emotions, consciousness, and self-acceptance. (Several neuroscientists consulted on the movie to help make it as accurate as possible.) I’ve done my best to avoid plot spoilers here and focus on the concepts.

In Inside Out 2, we learn that 13-year-old Riley’s five core emotions—Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust—have begun to oversee the construction of her “Sense of Self,” which grows from the beliefs created by her emotional experiences. For example, when Riley helps a classmate who has dropped a jar of coins in front of the class, Riley forms a joyful memory, which creates a belief that vibrates with the words, “I am a good friend.” Every time a new belief is added, Riley’s Sense of Self glows with the words, “I am a good person.” Joy only allows positive memories to enter the belief system, banishing the rest to the back of the mind.

Then, Riley’s puberty alarm goes off, and four new emotions join the crew: Anxiety, Envy, Embarrassment, and Ennui (boredom). The new emotions initially hang back. But faced with the prospect of social isolation, Anxiety takes over. She launches Riley’s “Sense of Self” out of headquarters to the back of the mind, and banishes the five O.G. emotions to a memory vault. The five core emotions go on a long journey through Riley’s mind to retrieve her “Sense of Self,” as Anxiety builds a new “Sense of Self” that crackles with the words, “I’m not good enough.” In the end, an emotional breakdown allows all of Riley’s suppressed memories, the original emotions, and her old “Sense of Self” to flood back into headquarters and the belief system. Riley’s new “Sense of Self” grows and includes both the good and bad aspects of Riley’s personality. The emotions gather around to give it a group hug, symbolizing self-acceptance.

During my Dark Ages, I—like Riley—was in “survival mode.” Anxiety ruled me, and I often felt that I had no control over my behavior, much less my thoughts. My reintroduction to joy—courtesy of Seven Lions—laid the foundation for my reconstruction.

During the summer of the Project Glow playlist, I started meditating here and there. It wasn’t something that I did with much intention—my work had started to offer free access to the Calm app, so I downloaded it. In September 2022, I started to meditate every day, following a meditation where I felt a similar sensation to a substance-induced high.

Music and meditation helped me exit “survival mode” and a “stimulus-response” pattern of behavior. Rather than reacting blindly to whatever the world threw at me, I began to recognize my capacity to pause. Stimulus-response became stimulus-pause-response.

While it’s impossible to disentangle the effects of music and meditation on my mental state, there is evidence that emotion and consciousness are related, which implies that music and consciousness are related, too. At a simple level, the same brain structures appear to be responsible both for emotional states and levels of consciousness (e.g., wakefulness, coma, vegetative state). In an experiment, participants were quickly shown happy, neutral, and sad faces, and happy, neutral, and sad words. Participants were more likely to perceive a face or word if it was happy, and more accurately identified happy faces and words as opposed to neutral or sad faces and words. This seems to imply that positive emotions can enhance our conscious awareness. This resonates with my sense that Seven Lions’ music helped me to feel joy, which increased my self-awareness (ability to pause) and self-acceptance.

Music’s capacity to affect our state of consciousness may go beyond self-acceptance and self-awareness. Perhaps music can help us understand esoteric ideas and certain states of mind.

For example, Subtronics’s “Scream Saver” sounds like an attempt to capture the sensation of having one’s mind blown. Before the drop, a male voice ominously says, “You’re already dead.” The drop itself is pulsating, glowing beams of energy: the sound of surprise and shock, the sound of realignment. It sounds like how it would feel to discover that the current experience is just an illusion and that death has already occurred.

During his Lost Lands set this year, Subtronics led into a Scream Saver remix following Galantis’s “Run Away,” a reminder that it is impossible to escape both uncomfortable ideas and death. The Scream Saver drops were more intense than the original, and I couldn’t do anything but close my eyes and raise my hands, assuming the starfish position as I took in the moment. My brain was completely devoid of words, but not of thoughts, per se. I was gently gripped by the experience, fully aware of my body and mind. In rewatching the set, I noticed that the visuals showed a succession of skulls, each replacing the last until a cyclops skull rather than a human one emerged and reached for the crowd. The audio-visual experience conveys an abrupt awakening, pairing mind-expanding sounds and lyrics with the image of the cyclops, whose third eye opened so quickly that it lost the ability to see with its original two.

Another example is INZO’s Overthinker, pairing wisdom from Alan Watts with unbelievable drops:

What is reality?

Obviously, no one can say

Because it isn't words

It isn't material, that's just an idea

Reality is-

The drop contains some of the most beautiful sounds I’ve ever heard in my life: it captures the feeling of spinning barefoot in a field of flowers, of running through the desert as the sunset paints the sky in vivid hues, of jumping into a loved one’s arms after a long time apart. When INZO dropped the VIP at Lost Lands, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

As I’ve exposed myself to this music again and again, I have felt further changes in my mental state. These are more difficult to put into words than the rediscovery of joy or the introduction of a pause between stimulus and response. For starters, I have begun to place more trust in my intuition, and it has shown itself to be reliable again and again. I have this sense—this inner knowing—that I am exactly where I’m supposed to be. And I have started to feel this push to create and to contribute my knowledge to our collective understanding, beginning with this question:

Why do we dance?

To understand why we dance, I wanted to first consider why we make music. Humans are not the only musical species—whales sing and chimpanzees appear to be able to perceive beats. As far as we know, however, we are the only species with a unified concept of music that includes melody and beat.

Deliciously, scientists do not agree on why music evolved in the human species. Popular theories suggest that music evolved to aid in communication, to attract mates, to help foster social cohesion, or to aid parents in bonding with their children. One experiment suggested that music can help resolve the discomfort of cognitive dissonance. But each of these theories has flaws, and the question remains open.

Scientists believe that music must have served an evolutionary purpose because its creation and consumption activate the same pleasure centers in the brain as eating, sex, and spending time with loved ones. It’s easy to grasp why food and sex are pleasurable: we need to eat to survive, and we need to mate to reproduce. It also doesn’t take a great leap of logic to understand why spending time with loved ones would be pleasurable. As the Starks from Game of Thrones would remind us, the lone wolf dies, but the pack survives. It is far less obvious why music would be important to our survival.

Perhaps we do not know why music evolved because it wasn’t previously important for our survival. Maybe music didn’t evolve because we needed it then. Maybe it evolved because we need it now.

Typically, the process of evolution leads to ecological balance. Consider cheetahs and the antelopes on which they prey. If the cheetahs could easily catch and devour the antelopes, the antelopes would quickly go extinct. If the antelopes were the cheetahs’ only food source, the cheetahs would then die of starvation. But we observe both cheetahs and antelopes thriving on the savannah, indicating that as the cheetahs got faster, so did the antelopes. To put it simply, the slower antelopes were eaten before they could reproduce. The two species could coexist only given this balancing act of adaptation and survival.

For much of our history, humans lived in a variety of ecosystems without causing their collapse. That began to change as humans developed more sophisticated tools and methods of coordination. Buffalo used to roam the North American Plains in great herds. They were hunted by some indigenous tribes, but the two species coexisted. When European settlers arrived with their guns and thirst for riches, the buffalo were hunted to near extinction.

Today, no other animals challenge the human species’ dominance. And yet, our society is still in survival mode. We have driven several plant and animal species into extinction. We have extracted resources from the earth and made large swaths of the planet inhospitable for any creature but ourselves. We have capitalism’d so hard that climate catastrophe looms large.

And yet, the process of evolution still trends toward ecological balance: just give it time. We may cause our extinction by making the Earth inhospitable for human life. We may surround ourselves with social media, fast food, and pornography, enslaved to our evolutionary drives. We may create another living entity with the power to crush and enslave us the way that we have dominated other less-intelligent animals.

Or, maybe not. Maybe it’s not too late to save our species and our planet. Maybe, if we listen closely, music will tell us how to save ourselves.

Now before I lose you, I want you to consider how artists talk about the process of creating art. Consider how Coldplay’s Chris Martin describes how the song “Yellow” came into being:

Like any of our really good songs, I had nothing to do with it. It just happened to arrive to me. We were recording in Wales at a studio called Rockfield in 1999 or early 2000, and I was recording a song called “Shiver.” I was doing this acoustic part, and the tape machine broke. I had no idea about all of the spiritual writing around things like “look at what’s missing as an opportunity,” or “the crack is where the light comes in.” But here it was on full display without me knowing it. There was a problem, something was broken, and it created a space for something cool to arrive.

I went outside, and I was with our producer at the time, Ken Nelson. He said, “Look at the stars.” It was such a beautiful night, and this studio is in the middle of nowhere, so the stars were so glorious. I went back in, and the tape machine still wasn’t working. I started to think about the words “look at the stars.” And I was like, Neil Young always makes the word “stars” sound so American. So I was messing around trying to sing like Neil Young — but my Neil Young sounds a bit like Kermit the Frog. Then I played a chord. I had no idea what the chord was; it sounded really nice. Before I knew it, this whole song just dropped through.

The title “Yellow” came from this phone book called the Yellow Pages. This whole song came from a mistake, a break, a dysfunctional piece of machinery, what happened to be lying around, and the stars themselves. It was just all a gift. I went through to where Jonny and Will were playing FIFA football in the lounge and I said, “Listen to this — what do you think?” They barely looked up. “Yeah, that’s all right.” It was a long time between that song arriving and us really knowing how to play it properly, but we kept going until it sounded like what you hear now.

The writer Anne Lamott similarly instructs aspiring writers to “listen to your broccoli,” playing off a Mel Brooks quote: “Listen to your broccoli, and your broccoli will tell you how to eat it.” Lamott writes…

It means, of course, that when you don't know what to do, when you don't know whether your character would do this or that, you get quiet and try to hear that still small voice inside. It will tell you what to do. The problem is that so many of us lost access to our broccoli when we were children.

Lamott and Martin speak of creating from some other part of themselves or something outside themselves. Some might say that they’re following their intuition. Others might say that some deeper power is communicating through them. I suspect that these are two ways to convey the same idea.

Music might be special because it is art that literally moves us. Listening to music recruits all sorts of brain areas: both obvious ones involved in auditory processing and less obvious ones involved with movement. You’ve probably felt an irresistible urge to tap your fingers or toes in the presence of an alluring beat, thanks to music’s effect on the motor regions of your brain. Music might be special because music makes us take action. It makes us dance.

I don’t have all the answers. Luckily, I don’t have to—understanding our reality is a collective process that will require many brains working together. What I do have is a mystical idea that we’re being called to save ourselves in the most fun way possible, starting with dancing to some of the most incredible, creative sounds to ever grace this planet. Dance might just open us up to love one another better. Dance might just remind us how interconnected we are. Dance might just quiet down our racing minds for long enough to hear the messages the universe has been dying to communicate with us.

To me, dancing is cosmically important. Do you feel it too?

Mia Arends loves writing and dancing—and thinks both are cosmically important. Follow her on Instagram, Threads, or X.

Some may write off music’s ability to communicate complex emotions, arguing that its complexity comes not from the sounds themselves but their cultural context. They would argue Beethoven’s fate motif only gives the listener a sense of foreboding because it has been used as a meme, plugged into movies, television shows, and other music again and again, always accompanied by other signals that communicate “FOREBODING.”

Culture certainly does influence our emotional interpretation of music. For example, in the West, major scales sound “happy” while minor scales sound “sad.” However, in the Middle East and parts of Southern Europe, minor keys are not strongly associated with sadness and can convey a variety of emotions.

Musicians, as members of society, are consciously or unconsciously playing with the associations and emotional resonance different types of sounds and patterns carry. This doesn’t negate music’s power to influence our feelings; it just suggests that each person’s interpretation of the same piece of music may be different. But people who share a similar culture are likely to share interpretations of music, as artists continue to play with and build upon others’ work.

This is really well written and thought provoking. Good for you for getting personal in the first part and telling your truth. 👍

beautifully said 💗